Envoy says dozens of countries will shun this year’s anti-racism conference at UN after past antisemitism; Bennett to make debut address at General Assembly next week

By TOI STAFF

Thirty-one nations will boycott a UN meeting marking the 20th anniversary of the Durban World Conference on Racism — also known as Durban IV — on Wednesday, over concerns that it will veer into open antisemitism as it has in the past.

The first Durban conference — held from August 31 to September 8, 2001, just days before the terror attacks of September 11 — was marked by deep divisions on the issues of antisemitism, colonialism and slavery. The US and Israel walked out of the conference in protest at the tone of the meeting, including over plans to include condemnations of Zionism in the final text.

At the 2009 conference, a speech by Iran’s then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad attacking Israel sparked a temporary walkout by many European delegates.

Thirty-one nations will boycott a UN meeting marking the 20th anniversary of the Durban World Conference on Racism — also known as Durban IV — on Wednesday, over concerns that it will veer into open antisemitism as it has in the past.

The first Durban conference — held from August 31 to September 8, 2001, just days before the terror attacks of September 11 — was marked by deep divisions on the issues of antisemitism, colonialism and slavery. The US and Israel walked out of the conference in protest at the tone of the meeting, including over plans to include condemnations of Zionism in the final text.

At the 2009 conference, a speech by Iran’s then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad attacking Israel sparked a temporary walkout by many European delegates.

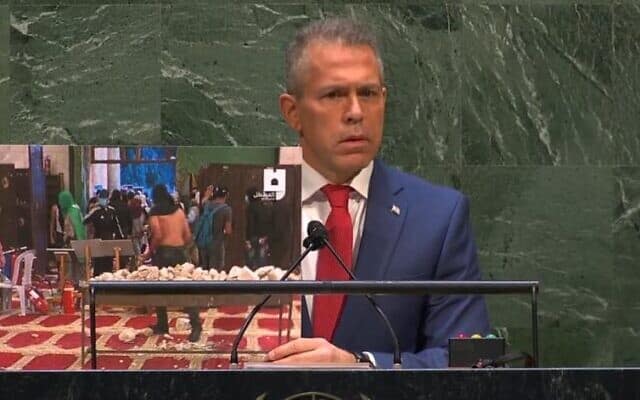

This year, Israel’s Ambassador to the UN Gilad Erdan said Friday, a record 31 countries will be skipping the event, over double the amount that have done so in the past.

“In recent months I have worked for the world to understand that the Durban Conference was fundamentally rotten,” he said in a Monday tweet. “I’m glad many more understand this today.”

The United States, Canada, the UK, Australia, and France are among some of the key nations set to boycott this year’s meeting.

Vaccines, climate, nuclear deal on General Assembly agenda

The highlight of the UN General Assembly, during which world leaders and other top officials deliver addresses from the marble-backed podium, begins on Tuesday in New York and will see a mixture of in-person speeches and pre-recorded video messages sent from around the world.

This year’s event and is markedly different from last year’s, which was conducted mostly online due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition to the speeches by world leaders, the General Assembly usually also has hundreds of side events, but only a limited number are being held this year, mainly virtually or outside UN headquarters.

These include events on vaccines, on children as invisible victims of the coronavirus and conflict, on multilateralism and democracy, and on global hotspots including Yemen, Somalia, Afghanistan and Iraq.

Additionally, the UN Security Council will hold a high-level meeting Wednesday on climate and security.

Afghanistan and other major global challenges are expected to be on the agenda, including the lack of progress on the United States rejoining the 2015 Iran nuclear deal.

Iran’s new foreign minister, Hossain Amir Abdollahian, will be in New York and there is speculation that he may meet with the five countries that remain part of the deal — Russia, China, Britain, France and Germany.

There are also high-level meetings on energy and the nuclear test ban treaty, and a summit on the connected system of producing, processing, distributing and consuming food, which according to the UN contributes an estimated one-third of greenhouse gas emissions.

Thirty-one nations will boycott a UN meeting marking the 20th anniversary of the Durban World Conference on Racism — also known as Durban IV — on Wednesday, over concerns that it will veer into open antisemitism as it has in the past.

The first Durban conference — held from August 31 to September 8, 2001, just days before the terror attacks of September 11 — was marked by deep divisions on the issues of antisemitism, colonialism and slavery. The US and Israel walked out of the conference in protest at the tone of the meeting, including over plans to include condemnations of Zionism in the final text.

At the 2009 conference, a speech by Iran’s then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad attacking Israel sparked a temporary walkout by many European delegates.

This year, Israel’s Ambassador to the UN Gilad Erdan said Friday, a record 31 countries will be skipping the event, over double the amount that have done so in the past.

“In recent months I have worked for the world to understand that the Durban Conference was fundamentally rotten,” he said in a Monday tweet. “I’m glad many more understand this today.”

France are among some of the key nations set to boycott this year’s meeting.

Bennett’s debut

According to a provisional list of speakers for the General Debate, US president Joe Biden will speak on Tuesday morning, in America’s traditional slot as the second speaker of the General Debate.

Prime Minister Naftali Bennett will be another one of at least 83 world leaders who plan on attending in person, according to Turkish diplomat Volkan Bozkir, president of last year’s gathering. Twenty-six leaders applied to speak remotely, Bozkir said earlier this month. Bennett will address the gathering on Monday, September 27.

In his address, Bennett will speak about Israel’s national security and regional issues, according to his office. His remarks will likely focus on Iran’s nuclear program and its support for armed proxy groups.

Bennett’s predecessor, Benjamin Netanyahu, was known for making headlines with his speeches on the Iranian nuclear threat at the UN General Assembly, often using cardboard graphics and other props to get his point across.

Israel’s regional partners will also be represented, according to the provisional list. Egypt and Jordan will send their heads of state, while the foreign ministers of Israel’s new Gulf allies Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates, will speak.

Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas and new Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi are both sending prerecorded addresses to be broadcast at the event.

https://www.timesofisrael.com/at-israels-prodding-record-31-nations-to-boycott-durban-conference-anniversary/